Long Term Plan threatens delivery of a remote, centralised NHS

Join us to protest against the Unfunded, undemocratic, unfair, unsafe plan, please share the Facebook event here.

Leaflet: NHS Long Term Plan: top-down disruption for the NHS

Thursday 31 January – 10am – 12pm

RALLY OUTSIDE

NHS ENGLAND BOARD MEETING

}Skipton House, 80 London Road

Elephant and Castle

London SE1 6LH

Here’s why:

It’s tempting to dismiss the NHS Long Term Plan, published on January 7 by NHS England [1], as an unrealistic wish list of developments completely divorced from the real constraints on resources. But it demands close analysis. There may be some messages that cannot be dismissed but they distract from the meat of the Plan. What is shocking is the virtual absence of discussion and proposals to address the severe problems facing the NHS. The major restructuring of the NHS goes forward at pace.

NHS England’s proposals will request that the government rescind regulations enforcing contracting requirements of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act that make CCGs parcel up services and put them out to competitive tender. This is a way of reducing the current market chaos 1000s of contracts in health care bring. But it does not by any stretch mean the exclusion of private profit – bigger centralised budgets may be up for grabs.

It is impossible to discuss the Plan’s content without also addressing the vital issues that are omitted from it and the diversionary list of service improvements that it freely promises.

Some positive concessions and considerable window dressing

There are a few positive concessions to the pressure of campaigners and the needs of patients:

- new waiting time targets are to be introduced for adult and child mental health, and funding is to be preferentially allocated to mental health – although with insufficient funding in total this implies cutbacks elsewhere;

- action to address unexplained mortality for people with learning disability and autism and the long waits they experience;

- Unlike many previous plans there is no explicit call to close acute hospital beds even if alternative services reduce demand for them – in order to scale down bed occupancy and stress on front line staff;

- There is even discussion of health inequalities;

- The idea is floated that the NHS take back responsibility for some public health.

And there is promise after promise of prompt response services, proactive care, flexible teams, neighbourhood teams, primary and community care teams, community multidisciplinary teams and upgraded support – all in happy-clappy, completely abstract terms.

Missing from the Long term Plan

The number of major issues that are either ignored completely or blithely brushed aside in the 136-page Plan is certainly enormous: they include the declining actual performance of trusts; the inexorable rise in emergency caseload; the insufficient capacity in acute and mental health services and bed shortages; the disastrous financial plight of most acute trusts; the workforce crisis compounded by the Brexodus of EU-trained staff; the £8 billion and rising bill for backlog maintenance; the damaging cuts previously inflicted in mental health and those ongoing in community services; the cuts in public health budgets; the widening gap in society between rich and poor and the resultant inequalities in health – exacerbated by unchanged austerity and reactionary government policies on housing, welfare, education, and local government: and of course the gathering crisis of a dysfunctional social care system.

The Plan, and its preceding Operational Planning and Contracting document, published on December 21, concede that they are incomplete: no workforce plan has yet been published, and there is no evidence to suggest that work on this has advanced at all; the “framework for implementation” is promised for “spring” – presumably spring 2019.

Moreover while we know from every informed observer that the famous £20.5 billion “extra” funding over five years announced three times last year is not enough to do much more than stabilise the NHS and keep the lights on, the amount of capital available to fund any substantial new projects will not be known until the Autumn Spending Review.

Nonetheless the December document outlined a break-neck pace for a clearly impossibly ambitious timetable for changes: the first deadline (14 January) for major decisions has already passed – just a week after publication of the Long Term Plan and 13 working days after the December document appeared. Managers are already running just to catch up.

With wholly inadequate funds, over 100,000 staff vacancies and no serious implementation plan, the Long Term Plan has to say something, and so it rattles out upwards of 60 uncosted commitments to improve, expand or establish new services, most of which if taken at face value would be most welcome – but which taken together in this context are completely unaffordable, unrealistic and incapable of implementation.

Pushing ahead to impose new structures

But these minor elements must not distract us from the hard proposals in the Plan for the top-down imposition of a new, centralised structure of 44 “Integrated Care Systems” by April 2019, which are to “grow out of the current network of Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships”, policed by regional directors and a network of ‘joint NHS England and NHS Improvement regional directorates’ who will only report upwards. (p5) ref

None of these new structures will be in any way accountable to the local people and communities they cover. Each ‘integrated care system’ (ICS) would work towards an ‘Integrated Provider Contract’ – along the lines proposed by NHS England and opposed by many campaigners in the consultation that ended last October: as was the case then, there is no guarantee that these contracts could not be awarded to or sub-contracted to the private sector.

Forced mergers of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)

The plan also requires more forced mergers of the existing Clinical Commissioning Groups to reduce to just one CCG per ‘integrated care system’ (ICS) – ensuring that current CCGs would be reduced to rump bodies with residual token power, accountable to nobody. CCGs are required to cut their management costs by another 20%. Trusts, too, would be required to collaborate with the wider ICSs.

Following along the model of the STPs that were hatched up in secret in 2016, none of these changes would be subject to consultation with staff or the public.

The break-up of primary care and forced mergers of GP practices

To add to further misery for many patients, GPs will be required to sign up to new “network contracts” covering populations of between 30,000 and 50,000, meaning that more local GP surgeries will be forced to close with services lumped together in centralised “hubs” offering less personalised and less continuity of care at longer distance for many patients – again with no prior public consultation or consent. This could see the 7500 practices cut back to 1500.

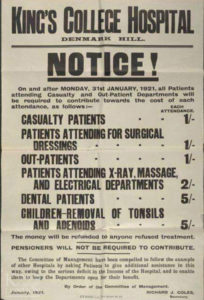

Extending the reach of privatisation and NHS charges

But tucked away are more hard-edged proposals that paint a very different and more threatening picture, with increased use of private hospitals to deliver NHS funded care (LTP p24 and already being actioned by NHS England under the radar), and pressure on trusts in the December document to increase their links with the private sector to “grow their external (non-NHS) income” and “work towards securing the benchmarked potential for commercial income growth.” (p12)

There is an implicit threat of privatisation in the proposals for huge new pathology networks and imaging networks to be established with no NHS capital available for investment.

Trusts must also aim to increase the funds they get from charging patients for treatment – “overseas visitor cost recovery” – raising little money in relative terms, but deterring some patients from accessing the services they need. This policy undermines the principles and values of the NHS, and is opposed by medical Royal Colleges.

Enforced fire sales of NHS estate

In December the Health Service Journal, revealed that NHS Improvement is applying pressure to trusts to seek one-off savings (including a fire sale of “surplus” land and buildings) to help them get closer to, or even lower the “control totals” which limit the level of their deficits. NHS Improvement has offered trusts a controversial incentive of £2 from ‘Sustainability Funds’ for every £1 reduction to their control total this year.

However NHS Providers has warned that this is most likely to benefit the already better-off trusts rather than those with the most intractable deficits.

Policing of cost controls

There is a decisive move to tighten up trust and CCG finances, with the aim of eliminating all deficits by 2023/24: the mid-year estimate was that trusts were £1.2 billion in deficit, in addition to long term borrowing from the NHS (bail-out funds) now at almost £12 billion.

Almost half of all acute trusts have refused to accept their control totals because of the scale of cutbacks required, while others are struggling to comply with theirs. The LTP now says the 30 most indebted trusts are also to be subjected to an “accelerated turnaround process”.

The December document made clear that CCGs with “longer standing and/or larger cumulative deficits will be set a more accelerated recovery trajectory,” while many would in any event be forcibly merged with others in the drive to establish Integrated Care Systems within two years.

For CCGs and providers alike, those with the toughest problems, and often with the most inadequate resources, face the hardest targets and the harshest treatment. This imposition of centralised control is the more worrying when coupled with the sweeping changes that are proposed to the type of care provided.

Changes to urgent and emergency care pose questions

There are proposals for a third type of emergency care, alongside Urgent Treatment Centres and the existing Emergency Departments: a poorly-defined system of “Same Day Emergency Care” is supposed to be rolled out to every hospital with a full A&E, aiming to discharge patients on the day of attendance. However it further fragments an already highly stressed service and requires significant investment in expanded diagnostic services: and there is no guarantee in the LTP that patients would get anything other than “assessment” before being packed off home to cut back community health and social care services.

Obsession with digital threatens fair access and data confidentiality

NHS England is also embarking on a mission to cut out a third of outpatient appointments (30 million fewer), on a series of questionable assumptions and citing only the medical specialties without addressing the needs of surgical patients.

Sweeping changes are proposed for how to access GP services: patients will be given a new “right” to switch from their existing GP to a “digital first provider” and all patients in England will be offered access to online or video consultations by 2023. There is no corresponding right to insist on a face to face consultation.

The obsession with digital access runs as a theme through the Plan:

“In ten years’ time, we expect the existing model of care to look markedly different. The NHS will offer a ‘digital first’ option for most, allowing for longer and richer face-to-face consultations with clinicians where patients want or need it.”

Unfortunately, this ignores recent research that showed Skype-type online consultations are suitable for only small minority (2-22%) of hospital outpatients, with many clinics finding them completely impractical. The NHS Plan insists on a vision that few patients would find attractive.

Unfunded, undemocratic, unfair, unsafe – unacceptable

Sadly it’s clear that with the financial constraints limiting any real improvement, and a new system being imposed from top down and accountable only upwards to NHS England, patients will have less voice and influence than ever in the shape of services and their access to them. Everything about us will be decided without us.

So despite the jolly phrases and the misplaced optimism of its tone the Long Term Plan is a medium term threat to the services we all depend upon and to our ability to fight locally to defend the services we need.

Join us to campaign to defend the NHS

Campaigners and union activists need to keep a very close watch on the decisions and actions of trust boards and CCGs as the NHS is pushed at reckless pace towards changes we cannot accept. We need more than ever to brief politicians and urge them to stand out against policies that will weaken local services.

Campaigners and union activists need to keep a very close watch on the decisions and actions of trust boards and CCGs as the NHS is pushed at reckless pace towards changes we cannot accept. We need more than ever to brief politicians and urge them to stand out against policies that will weaken local services.

John Lister, co-chair KONP and Editor of Health Campaigns Together

KONP’s demands

- Health campaigners continue to argue vigorously against a market in NHS care.

- We demand that the NHS should be publicly provided and brought back fully into direct and accountable public management

- We opposed the fragmentation created by the 2012 Act

- We are opposed to handing over control of the NHS to new unaccountable public-private alliances and private companies.

- We call for an end to charges for overseas visitors and checks on patients to restrict entitlement

- We support the NHS (Reinstatement) Bill that would achieve these demands

For more information see Our Aims

Join us to protest against the Unfunded, undemocratic, unfair, unsafe plan, please share the Facebook event here.

Thursday 31 January – 10am – 12pm

RALLY OUTSIDE

NHS ENGLAND BOARD MEETING

}Skipton House, 80 London Road

Elephant and Castle

London SE1 6LH

[1] NHS England oversees the budget, planning, delivery and day-to-day operation of the commissioning side of the NHS in England as set out in the Health and Social Care Act 2012. It is now merging with the regulator, NHS Improvement.

Don’t agree with your demand to stop charging overseas visitors. NHS needs all the money it can get.

Thanks Danny for your comment. The truth is that the amount of money in question is around £70 million out of a budget of some £125 billion. The cost of setting up the charging mechanisms and workforce to ensure the imposed charging is carried through more or less negates the impact. However, a negative regime is put in place, challenging people’s right to treatment and frightening many people who need help into delaying seeking help or avoiding it entirely. Please have a look at our leaflet on this subject: https://keepournhspublic.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Health-Tourism-facts.pdf. Bevan saw the principles of the NHS as an advertisement to the world for what a progressive society could achieve in providing an excellent health service for all. He felt that was worth it, rather than regimes of checks and charges.