This article was originally published on OpenDemocracy's OurNHS section, and is republished here with the kind permission of the author.

Today was the government’s big chance. A chance to show its mettle. A chance to improve our collective resilience to the health and economic impacts of the coronavirus. To protect and reassure an increasingly uneasy populace.

But it has missed that chance. The chequebook might have been waved around more than in recent years, but too much of the same old mean-spirited, laissez-faire thinking was still on display.

The government said in announcing today’s budget that it “stands ready to provide further support, should it be needed”. It is needed. Both to improve our chances of avoiding the worst consequences of the coronavirus, and to begin to address some of the searing injustices of the last decade. A real ‘levelling-up’ to match the prime minister’s promises.

One of the most obvious gaps in our collective resilience is our shredded social security net: there are widespread concerns that the millions who currently get little or no sick pay won’t be able to afford to self-isolate. So what did the Budget have for them?

Not much. For the large numbers of people who don’t have occupational schemes and rely on Statutory Sick Pay (SSP), that remains at £94.25 a week: less than a third of the full-time minimum wage. The 2 million part-time and zero-hours workers who currently don’t qualify for even that payment, still won’t qualify. The 5 million self-employed still won’t qualify either.

Both these groups will be entitled to just £73.10 a week – £59.90 for under-25s – payable through either Universal Credit or Employment and Support Allowance (ESA). Whilst those with children may get more, there are also gaps that mean some will get nothing at all.

The only significant changes are that SSP has become slightly easier to claim without a GP visit, and that SSP and ESA will now cover people from their first day of sickness rather than their fourth or eighth day respectively. Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced a “change” to Universal Credit, but it is merely a confirmation of existing practice, which allows some recipients to continue to get the benefit when they’re sick.

Today’s Budget still leaves millions of relatively hard-up people facing an enormous hit to their income if they are sick or need to self-isolate. And despite Sunak’s boast that this was “the most comprehensive economic responses of any government anywhere in the world, to date”, the measures compare poorly to those introduced by other governments.

Compare Ireland, for example, which has just dropped the contributions requirement on its sickness benefit so that the self-employed and low-paid can get it too. Not only that, it has increased sickness benefit by €100 a week, to €305 a week (around £266). Which is a sum that people could vaguely live on, and comparable to sickness pay and benefit schemes across the rest of Europe.

The UK can and should do something similar – a dramatic hike in both sick-pay rates and eligibility – immediately. Far from hitting the economy, such a patch to the broken sick-pay system would be an economic stabiliser against a major hit on consumer spending, as poorer people tend to spend their money rather than hoard it. Driving the poor into further poverty benefits no one but the loan sharks. Boosting sick pay would ensure that – as Boris Johnson promised last week – no one is “penalised for doing the right thing” in staying at home to protect both the population and the NHS from the virus.

But is the government capable of such a mindset shift, after a decade or more of attacking the sick as shirkers? Even away from today’s disappointing Budget, there are worrying signs it may not be. The Times reports that advice for those with colds to self-isolate has not been introduced yet “because modelling suggests it would seem like crying wolf”, adding that “there are concerns that some could use it as an excuse to avoid work”. The Times article appears to suggest that the modelling derives from the controversial ‘Nudge Unit’.

Possibly the stupidest measure in Sunak’s Budget was the announcement that the ‘migrant surcharge’ has been increased to £641. This is the charge introduced a few years ago that migrants must pay to retain eligibility to use the NHS. It will also extend to European nationals from January next year. This is stupid because the scheme requires huge bureaucracy to administer and raises little money. It is more about posturing to the Tory base and scapegoating migrants for the NHS’s ills than it is about sensible finances.

It’s also stupid because the far more sensible thing to do in response to a public health crisis would be to announce an immediate suspension of the whole of Theresa May’s pointless and cruel NHS charging regime on migrants. This includes a range of charges, not just this surcharge, and leaves many UK residents scared of accessing health services when they need to. In theory, these charges are suspended if migrants are suffering from severe infectious disease like the new coronavirus. But when you’ve spent eight years deliberately cultivating a hostile environment, that fear isn’t going to turn off overnight without a big and bold statement. Sunak’s announcement goes in precisely the opposite direction.

Oh, and it’s also stupid because the surcharge applies to the many foreign nationals who currently work in the NHS, and we’re likely to be relying on them rather heavily in the months to come.

If not now then when?

A threat from a virus should remind us that what we have in common is humanity, and we can only solve this by improving collective resilience – we’re only as strong as our weakest link. So the government needs to start addressing the economic (and legal) inequalities that undermine that collective resilience.

The measures I’ve suggested – raising the level of sick pay from its current paltry level, extending its eligibility to the self-employed and low earners, and suspending the NHS migrant charging regime – could be implemented quickly and would help limit the spread both of the virus and of anxiety. But so far, it seems the government lacks the political will. Common sense is lagging behind decades of knee-jerk shirker- and migrant-bashing.

Others measures vital to improving our collective resilience will take time, as well as political will. It will take time to tackle the austerity-mediated decline in poorer older people’s life expectancy, and their vulnerability to disease. And to clean up the dirty air that’s already taken three years off average life expectancy and weakened people’s respiratory and cardiovascular systems.

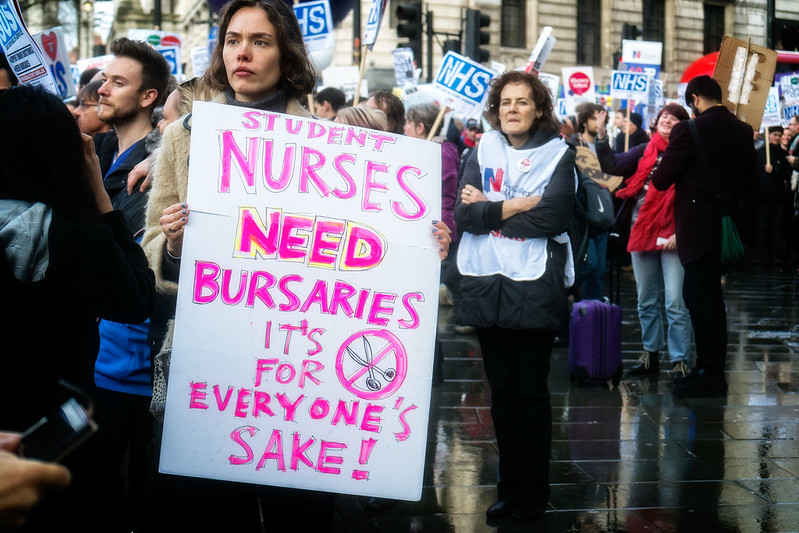

Most alarmingly right now, it will take time to reverse the dramatic shortages in trained NHS staff, after what Helen Buckingham, director of strategy and operations at the think tank Nuffield Trust, calls “10 years of underfunding and a failure to understand staffing”. No one thinks we’re going to be able to replicate the Chinese government’s feat of building and somehow staffing hospitals in a matter of weeks.

But time, of course, is one thing we may well not have much of – particularly if the government continues to drag its feet on limiting the spread of the virus.

It’s estimated that up to 80% of the population are susceptible to the virus and that 5% of those who do may need intensive care. That’s about 2.6 million people, in a worst-case scenario. The NHS has only around 4000 intensive care beds, and about four-fifths of them are already occupied. For those requiring hospitalisation but not intensive care, the problem is the NHS has lost far too many beds in the last 10 years and currently has 43,000 nurses fewer than it needs, as large numbers leave a demoralised service.

Sunak’s budget has a £5 billion fund to assist the NHS, councils and other public services deal with COVID-19, as well as £6 billion to begin to meet the government’s manifesto promises over staffing and new hospitals. Those figures will of course need to be unpicked over the coming days to see if it’s genuinely new money and how fast it is likely to materialise.

But however hard the NHS works to tool up, the maths and the timescales are scary. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we are going to find out what happens after successive governments weaken our safety net and public services over decades. The poor and marginalised are, once again, the ones who are going to be left with the toughest choices. But no one is going to be able to dodge the impact.

Perhaps it’s not too late for enlightened self-interest to kick in, though. That was, after all, the principle upon which earlier incarnations of the welfare state were founded, when Victorian and Edwardian poverty and disease started affecting the lives of the urban middle classes.

It’s time for fast fixes, as well as solutions for the long haul. If not now, then when?

Leave a Reply