by Mark Thomas

Mark Thomas is the founder of the 99% Organisation. He is author of 99%: Mass Impoverishment and How to End It (FT Best Books of 2019) and lead author of The Rational policy-maker’s guide to the NHS (2023).

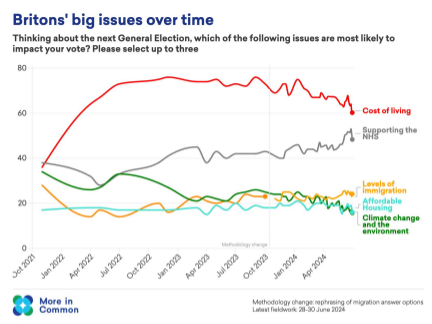

We British prize the NHS highly – and we consistently say that we want our politicians to protect and rebuild it. In fact it is the #2 issue, behind tackling the cost-of-living crisis, that (before the election) we said we wanted the new government to address.

This means that public figures who oppose the NHS on ideological grounds usually dare not say so outright: they tend instead to claim that the NHS as we have known it has become unaffordable and that we therefore need a new model. Many politicians insist that they would dearly love to fund the NHS adequately but “cannot afford it” – at least not right now.

There are three main variants of this claim, none of which bear serious examination:

- Empty soundbites, which sound reasonable only until you think about them

- A claim that reasonable things are affordable, but not the NHS

- A claim that nothing is affordable right now – with a £22billion black hole, we just don’t have the money – and the NHS will have to take its share of the pain

Empty soundbites

There are many variants of the idea that simply spending more over time is somehow unsustainable: ‘The NHS is like a black hole; we can’t just keep pouring more money down it year after year.’

Here, for example is a headline from Bloomberg: ‘Britain’s NHS Black Hole Is Devouring the Whole Country.’

Phrased like that, and in a supposedly reputable news source, it sounds scary. And this kind of emotionally resonant wording is persuasive to many people – including some policy-makers.

But in the real world, two important things are true:

- The economy grows in nominal terms virtually every year

- Inflation is greater than zero virtually every year

The result of these two simple facts is that we do spend more in cash terms over time on almost everything: more on food, more on energy, more on clothes, more on housing, more on technology, etc. In the real world, it is inconceivable that we would not also spend more on health, as we (and every other country) have done in the past.

Although such sound-bites may seem an unserious way of arguing, that should not influence policy, they pack a powerful emotional punch and can have serious effects.

‘Reasonable things are affordable, but not the NHS’

Once we realise that spending more money over time is the norm, we are less likely to believe that the NHS is unaffordable – unless there is something special about the way its costs are growing.

So, a more sophisticated approach is to claim that there is something special. Here is the former Health Secretary, Sajid Javid, explaining in breathless terms why a growing and ageing population means that cost pressures will race ahead uncontrollably:

‘Both men and women can expect to live more than a decade longer than they did in 1948. Back then, less than 1 percent of the population lived past the age 80. Today, we have 3 million people over 80 – predicted to rise to 4.4 million by the end of this decade. … As the IFS has shown, treating an 80-year-old is on average four times more expensive as treating a 50-year-old. … Taken together, it’s clear that we were always going to come to a crossroads: a point where we must choose between endlessly putting in more and more money, or reforming how we do healthcare.’

This is superficially more plausible than an empty soundbite as it is built on a partial truth: older people do cost more on average than younger ones. But that is largely because many more of them die. The last few months – and in particular the last month – of life tend to bring very high healthcare costs. Relatively few 50-year-olds die; many more 80-year-olds do – but they only die once. So, an ageing population has a far smaller effect on healthcare costs than Javid would have us believe.

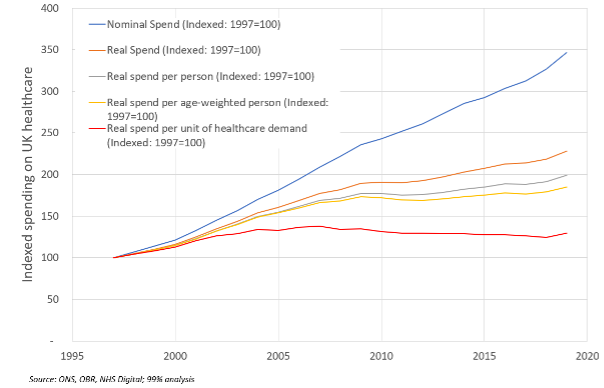

The chart below, from The Rational Policy-maker’s Guide to the NHS quantifies the drivers of UK healthcare costs, so that we can gauge the relative impact of the different factors.

The top line shows nominal spending on the NHS – ignoring the effects of inflation, population growth, population ageing and increasing rates of ill-health among the population. If one ignores all those things, it looks as though the NHS has been reasonably well funded. But of course, ignoring these vital factors would not be rational. The second line from the top (orange) shows what a huge bite inflation has taken out of the value of NHS funding. The third (grey) line shows the impact of the increasing size of the population – which also makes a significant difference. The fourth (yellow) line shows the impact of ageing of the population, and it makes a surprisingly small difference. And finally, the bottom (red) line shows the impact of rising rates of ill-health within age bands – and this is almost as significant as inflation. It shows that, once you adjust for the level of demand, healthcare spending has actually been falling.

In terms of affordability, which of these should a government worry about? Not inflation, as government revenues also rise with inflation; and not the growth in the population, for the same reason. Ageing of the population is a small issue. So the real concern should be the increase in ill-health within age groups.

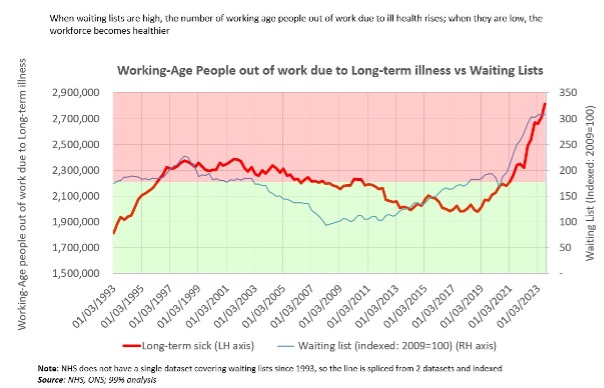

The Review by Sir Michael Marmot and others has shown that rates of ill-health are driven largely by social determinants such as poverty, poor housing, diet and stress levels. As the chart below shows, these rates are themselves unaffordable – because of the cost to the economy of working age people dropping out of the workforce.

So The Rational Policy-maker’s Guide to the NHS concluded that policy should be to fund the NHS in line with need, to invest in preventive healthcare and to tackle the social determinants of ill health. If the NHS is allowed to fail through underfunding or other factors, it concludes, the UK economy will fail with it.

‘We just don’t have the money’

There is one final argument against adequately funding the NHS: that all of the above may be true, but ‘money doesn’t grow on trees’. With the state of government finances as it is, we simply cannot afford to spend more on anything, no matter how high a priority it is.

This is a different kind of argument: one about the nature of government finances rather than about the NHS itself. But since it is so popular among politicians, we should explore it, too. It is an argument often made by those who claim that government finances should run like household finances. Although this claim is economically illiterate, it remains quite common and many politicians, including the current chancellor, still talk about balancing the books[MOU1] .

This argument runs: we can spend when our finances are in good shape, but right now there just isn’t the money. This was Cameron’s argument for austerity: ‘There is no magic money tree’. But strangely, when it needed money to prevent a collapse in the banking system, his government – via the Bank of England’s Quantitative Easing programme – simply created around £445 billion of new money. Money that it had been saying it did not have. And again, during the COVID lockdown, the Government created around £450 billion more to prevent a collapse in household finances when people would otherwise have had no income. Also at a time when the Government had been saying that it ‘had no money.’

In total, during the 21st century, the Government has created £895 billion of new money – it did so whenever it had the will to do so. Being able to do this is an enormous benefit of running a fiat currency system, but one which commentators tend to ignore.

Conclusion

If there is a financial emergency, the Government can use Quantitative Easing to fund the NHS, as previous governments have used it to tackle their emergencies. If there is no emergency, the Government can fund the NHS through a combination of borrowing and taxation in the normal way. Either way, the only thing that would be unaffordable would be to allow the NHS to fail.

As John Maynard Keynes wrote in 1942:

‘Assuredly we can afford this and much more. Anything we can actually do, we can afford. … We are immeasurably richer than our predecessors. Is it not evident that some sophistry, some fallacy, governs our collective action if we are forced to be so much meaner than they in the embellishments of life?’

The sophistry and fallacies are still with us more than 80 years after Keynes wrote that.

But we do not have to believe them.

[MOU1]Including the current chancellor?

Leave a Reply