Obituary by John Lister

[John is co-chair of Keep Our NHS Public and editor of Health Campaigns Together]

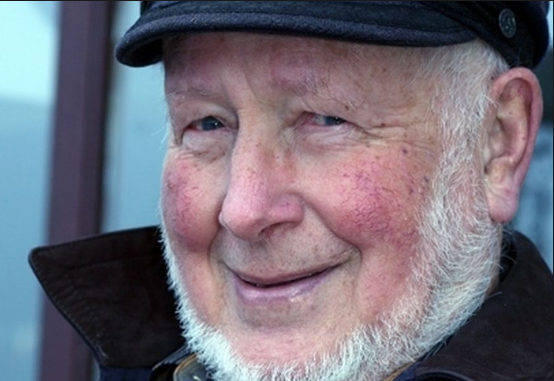

Dr Julian Tudor Hart, a founder member of the Socialist Medical Association and the first honorary President of the Socialist Health Association died on July 1, aged 91, in the week of the 70th anniversary of the NHS, which he fought so hard to improve and defend.

His death is a sad loss to socialists and campaigners: but his life’s work has left us better equipped to address health inequalities, and to understand the weaknesses and contradictions that limit the effectiveness of the NHS.

Although he was best known for the memorable phrase and approach of his 1971 Lancet paper on The Inverse Care Law, Julian was at the same time a consistent and relentless critic of the impact of markets on health care, which were also central to the same keynote article almost twenty years ahead of Margaret Thatcher’s government’s legislation establishing an ‘internal market’ in the NHS.

The opening abstract (summary) of that article is an example of Julian’s always compressed and lucid writing style and his skill in the brief exposition of a complex concept:

The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served. This inverse care law operates more completely where medical care is most exposed to market forces, and less so where such exposure is reduced. The market distribution of medical care is a primitive and historically outdated social form, and any return to it would further exaggerate the maldistribution of medical resources.

These linked themes so succinctly set out in 1971 have formed a near constant focus for campaigners and progressive academics since the late 1980s. Indeed, the concept can be read more broadly to argue that those with the greatest health needs are almost always those least able to afford the market price of health care as a commodity; and it can explain why those areas facing the greatest deprivation are always those with the least political power to force change.

However, Julian in his later years was increasingly reluctant to refer to the inverse care law. We might say that the importance Julian himself attached to the concept and the phrase was inversely proportional to the common acceptance and use of the term. He argued that the inverse care law detached from the wider social and political critique was relatively trite and unimportant.

He was angered by the ways in which the concept had been effectively devalued and hijacked by managers and establishment politicians seeking to claim a fig-leaf of concern for health inequalities while pressing forward with policies to deepen and entrench the purchaser/provider split and market mechanisms in the NHS.

For Julian, the key question was not neat phrases and clever argument, but testing and proving ideas in practice, improving not only the work of GPs but the social and organisational context in which they worked.

He worked for 30 years as a general practitioner in a health centre in Glyncorrwg near Port Talbot in South Wales, which became the first recognised research practice in the UK and pioneered the regular monitoring of blood pressure, proving it could help reduce strokes and premature deaths in high risk patients.

It was also characteristic of Julian to reject hierarchical notions of the GP or doctor standing above other health staff: he insisted that the doctor could only function effectively and fully as part of a team, and his research on blood pressure and other medical issues always stressed the importance of high quality records, teamwork and audit.

For Julian’s later work the concept of the team was widened still further, to include the role of the patient, who, he argued had to be seen as a principal factor in the “co-production” of improved health. This led on to the importance of continuity of care, which has just been underlined by recent research – at the same time as the latest faddish preoccupation with using apps and online consultations serves to weaken the links between GPs and patients. Julian wrote in 1994:

Continuity is not in practice valued in a competitive market, in which consultations are seen as isolated providers-consumer transactions, scattered between competing providers. (Feasible Socialism, p47)

He also emphasised the necessity of doctors (who had been shown on average to interrupt a patient after only 18 seconds of asking them why they had come) listening to patients rather than diverting them with premature questions:

Studies of medical out-patient consultations show that 86% of diagnosis depends entirely on what patients say, their own story. What doctors find on examination adds 6% and technical investigations (X-rays, blood tests, etc.) add another 8%. To most lay people and even some doctors these figures are astonishing, the reverse of the proportions expected. (Feasible Socialism, p 42).

As a fierce critic of the competitive market developed by New Labour from 2000, Julian was one of the founding members of Keep Our NHS Public in 2005. His most substantial book-length study The political economy of health care was first published in 2006, with a revised second edition in 2010. The mixture of Marxist analysis and clinical perspective mean that passages can be a less easy read than Feasible Socialism, and Julian was never quite satisfied with it, but the book offers many useful insights.

Julian was also active in collaboration with many experts and academics internationally, and a leading figure in the International Association of Health Policy in Europe (IAHPE): the last time I saw him speak in a public forum was at an IAHPE conference I organised at Coventry University in June 2009.

In his later years Julian became less confident of his ability to set out an extended and detailed argument in writing, and the last time I met him, for lunch at a restaurant in Swansea, he persuaded me to take on the production of a book on the clash between professional ethics and the market, and the problems in developing and maintaining patient-centred care.

However, this was just at the point that work began to launch Health Campaigns Together and the task fell by the wayside: Julian’s death is a powerful reminder of the need to return to this task and deliver a book worthy of its originator.

Many will miss the inspiration and support we had from Julian, who was a quietly spoken, friendly but steely-willed ally, with a complete commitment to quality health care and a far-sighted Marxist understanding of the contradictions of the health care system that has arisen after almost four decades of efforts to undermine the principles of the 1948 NHS.

But he and his work will not be forgotten as long as campaigners fight to defend, reinstate and improve the NHS and health care.

Leave a Reply